Why discipline, teamwork, and training still trump technology in mitigating brownout risk.

Brownout is the lifting of fine particles of dust or snow by helicopter downwash during take-off or landing which completely obscure the visual references of the pilots. It can quickly lead to disorientation and loss of control. In 2012, NATO published a technical report titled Rotary-Wing Brownout Mitigation: Technologies and Training. Compilation of the report coincided with the high point of combined operations in the deserts of Afghanistan, where that same year while on operations with the Royal Navy, I was in command of one of the many allied helicopters flying there. My own training had taken the threat of recirculating dust very seriously. And with good reason. Brownout was the number one threat to helicopter operations in the desert environment, even during combat operations. Between 2001 and 2007, the US Army alone linked 40 out of 50 helicopter mishaps in the desert to the phenomenon. During NATO operations in both Afghanistan and Iraq it contributed to three-quarters of coalition helicopter mishaps. The numbers are sobering.

In an attempt to address this threat, a multi-year study into the effects of dust and snow recirculation on military helicopter operations was carried out, and the resulting report remains one of the most comprehensive examinations of the hazard to date. It collated experiences from nine nations operating in some of the most hostile environments on earth. Although the focus of the 2012 report was on military operations, the lessons it holds are still relevant for civil rotary-wing flying, especially for tasks like HEMS and SAR, or utility work in remote areas. For civil pilots, the operating environments may differ somewhat but the physics do not. Fine dust, loose sand, or snow will obscure references just as effectively whether in a desert LZ, a rural landing site, or a mountain snowfield. Only last year an AW139 on a HEMS mission in Portugal crashed in brown-out conditions while attempting a landing at an unprepared site in a quarry.

The NATO study examined the factors leading to brownout events and the best strategies available to avoid them. What emerged is clear: brownout is not primarily a technological problem; it is a human factors problem. Technology can and does help. In the long-term, full synthetic vision systems may even hold the answer to eliminating the risks of degraded visual environments altogether. But until then the decisive layer of safety remains the crew, through disciplined preparation, coordination, and application of mitigation strategies before and during landings and take-offs. This article extracts some of the key points in the report and walks through the strategies recommended to combat brownout from pre-flight planning to in-flight execution, but always keeping the human factors at the centre of risk mitigation.

Anticipating the Threat: Understanding illusions and human limitations

There’s lots of research demonstrating how pilots are vulnerable to powerful illusions in degraded visual environments. Brownout doesn’t just blind you; it actively tricks you. The most dangerous of these are:

- Undetected drift. Slow lateral drift below vestibular thresholds may go unnoticed until it’s too late.

- Vection illusion. Moving dust can make you feel as though the helicopter is sliding in the opposite direction.

- Somatogravic illusion. Acceleration or deceleration can be erroneously interpreted as a pitch attitude change.

There’s lots more detail on the physiological and perceptual effects in chapter 2 of the report for those wanting a more in depth understanding. Link to study

Just knowing that these illusions exist won’t stop them from occurring. What matters is developing disciplined responses. That means relying on instruments and symbology where available, backing them up with crew calls, and mentally rehearsing transitions so that if visual cues do disappear, the crew already know exactly how to react and what to expect from each other.

Pre-Flight Planning: Reducing the risk before you launch

Brownout risk begins with assessing the landing site. Civil operators usually (not always) have the luxury of time for planning, and often the ability to choose a surveyed zone. Hazard anticipation plays a key role to avoiding the problem in the first place and, if it is possible to do so, this process should take place well in advance of the flight.

Landing zone assessment. Loose, fine sand or powdery snow is the perfect recipe for recirculation. If there is any possibility to choose a surface with more cohesion – gravel, grass, hardened ground – it will pay dividends.

Wind direction. Always plan to approach into wind if at all possible. Even light winds will carry dust away from the cockpit, improving references, and delaying the onset of total obscuration. Remember that any kind of downwind component will have the opposite effect and is asking for trouble.

Go-around planning. If there is a risk of brownout, every approach should be treated as provisional until the aircraft is on the ground with rotors at minimum pitch. Pre-identify your escape path, consider terrain and obstacles, and be ready to execute a go-around without hesitation.

Crew briefing. This is where civil crews can learn directly from lessons hard-learned by the military. Reiterate before descent:

- The role of the pilot flying.

- The SOP for monitoring drift, height, power, and other relevant parameters.

- The standard patter expected from the rear crew (if available).

- Most importantly: anyone in the crew can call for a go-around. Flatten the authority gradient before you enter the dust.

In-Flight Techniques: Choosing the right approach

The report emphasises that there is no single “safe” brownout landing technique. Each has strengths and weaknesses and needs to be tailored to the environmental and topographical – and sometimes operational – conditions at the approach and landing site. What matters is selecting the right one for the circumstances encountered and committing to it with discipline and shared mental models.

Whatever technique is used, two principles are universal:

- Stabilize early. Enter the dust with minimal drift and a steady profile.

- Go-around immediately if unstable. Delaying this decision has been the downfall of many crews. Once references are lost, even momentary hesitation can lead to disaster.

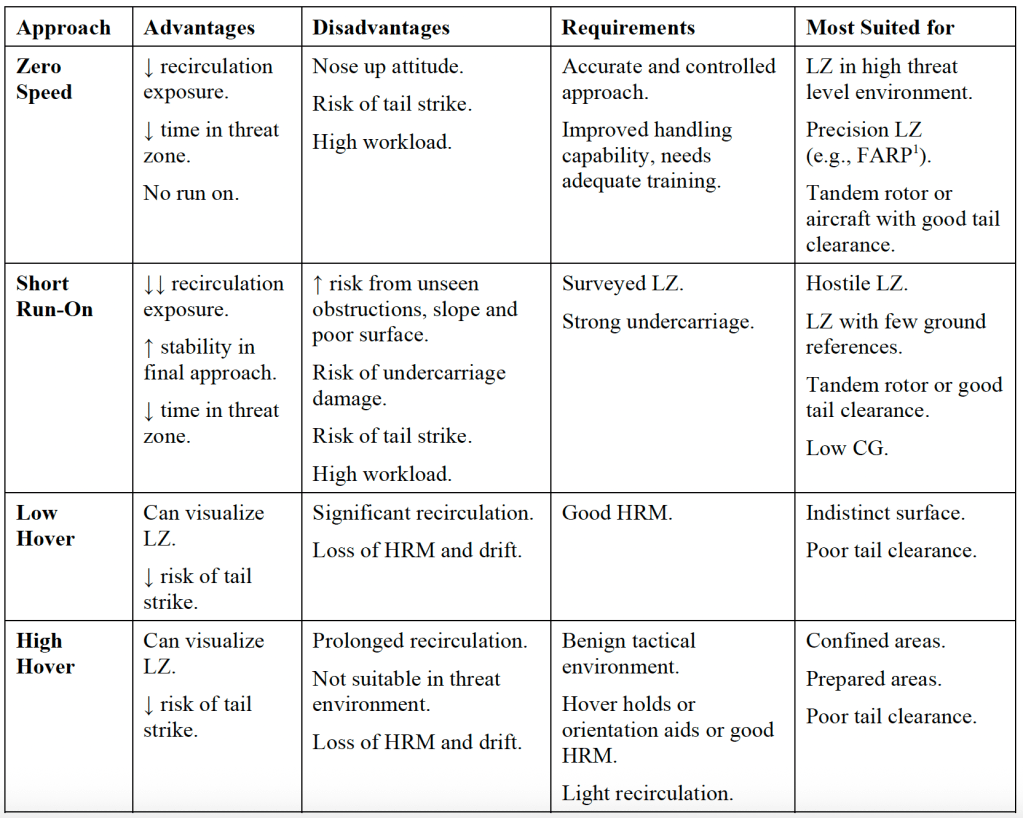

Four types of approach are discussed:

- Zero-Speed Landing. Precise and controlled, it minimises time in the dust by keeping the building cloud behind the aircraft until the touchdown point. But it requires training and demands a higher skill level. It also carries a greater risk of tail strike in certain aircraft types.

- Short Run-On Landing. This also has the advantage of keeping the dust cloud behind the aircraft. It allows a more stable and easily flown approach but depends heavily on the surface at the landing site and increases risk from hidden obstacles and undercarriage loads .

- High Hover and Vertical descent/departures. This approach can be useful in confined areas, and is sometimes required to conform to Performance Class 1, but it requires Hover Out of Ground Effect power and carries a greater potential for lifting dust. It is important therefore to consider that loss of references may be a greater relative risk to that of power loss. This approach envisages a vertical or near vertical descent, pausing at step down heights to allow assessment and dissipation of dust.

- Low Hover and Land. This approach might be required if the crew is uncertain about the quality of the landing surface at an unfamiliar site, but should be avoided if possible as it can create the most intense dust recirculation and disorientation. If this approach is chosen then underlining the role of crew co-ordination and an early call to go-around is even more important.

Table1 below extracted from the report (Table 5.1 Comparison of landing techniques, pg. 5-8) summarises the pros and cons of these and when each might be most suitable.

Table 1. Comparison of landing techniques

Emergent technologies and the search for a solution

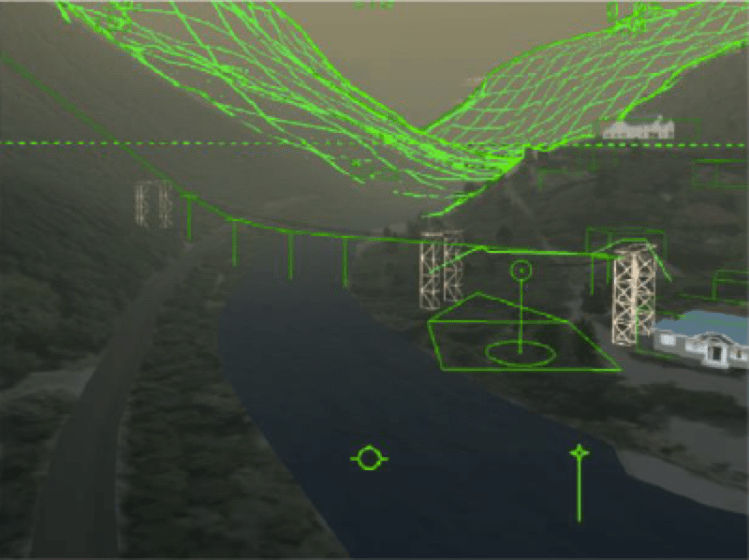

The meat of the paper concentrated on a review of a wide range of technological solutions to brownout, both mature systems already trialed and emerging technologies. These technological developments fall into two categories according to which problem they are trying to solve: For aircraft control and stabilisation, the enhancing of aircraft state awareness, including drift, groundspeed, height above ground, rate of descent, and attitude; for Landing Zone awareness, providing pilots with more information about surface, surrounds, size, shape, slope, and hazards and obstacles through the dust.

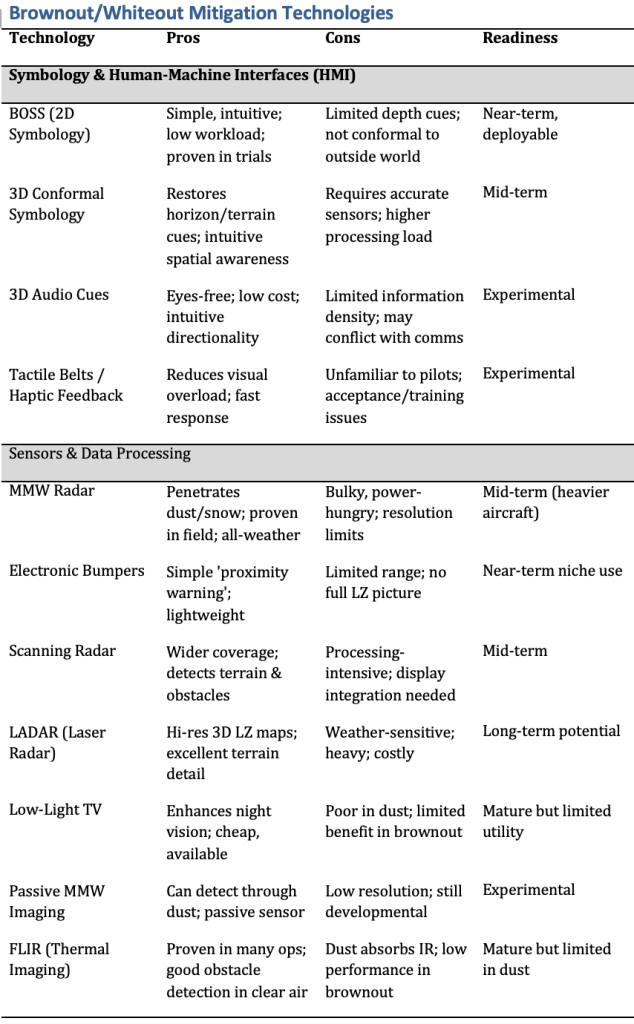

Four types of technology were explored:

- Symbology & Human-Machine Interfaces (HMI) to replace missing external references in dust/snow with reliable internal cues.

- Sensors & Data Processing capability to overcome the biggest challenge in brownout by ‘seeing’ through the cloud.

- Display and cockpit integration to make displays intuitive and low-workload – clutter or excessive data increases risk.

- Automatic Flight Control Aids & Automation. The holy grail is to let the aircraft handle the most dangerous part of brownout – the last few seconds of a landing – all by itself.

Table 2 gives a summary of the technologies evaluated as well as the assessment of the task group on their maturity.

Table 2. Brownout/Whiteout Mitigation Technologies

The report’s conclusion was stark: it’s an evolutionary process, and until technology matures, the only reliable immediate mitigation lies in human factors. From laser radars to haptic cueing many of the systems showed much promise. Sure enough, now thirteen years on from when this was compiled some of those listed have advanced leaps and bounds. Nevertheless, in 2025, for most civil helicopters and their crews, the conclusions of the authors remain valid: the future will undoubtedly bring better sensors and synthetic vision, but it is still around the corner.

Training: building confidence and competence

So, if managing brownout risk remains (for the time being) primarily a human factors problem, the answer to reducing it lies principally in crew training. To be effective, brownout training needs to go beyond ground briefs and theory. NATO’s military experts stressed the importance of a progressive approach. My own training followed this pattern. I began by practicing the flight techniques, standard con, and crew co-ordination flying to a point on a runway at my home airfield. From there it progressed to the coarse sand of dunes behind a British beach, and then to the fine dust ground up by heavy vehicles in a military training area on the plains of central Spain, before I finally deployed to the Afghan desert. Once in Afghanistan, we still practiced the techniques by day and by night every month to remain current.

Adapted to the realities of civil operators effective brownout training might look a little like this:

- Theoretical and classroom training. Understand illusions, human limitations, develop and brief standard procedures.

- Synthetic training. Use simulators to practice standard crew communication, work-cycles and workload management, flight techniques and go-arounds in a safe environment.

- Live training. Begin practicing flight manouevres in benign dust or snow conditions in a controlled manner, gradually increasing difficulty to engrain crew procedures and motor programmes in a real flight environment.

- Continuation training. Degraded visual environment landings and departures are an advanced level manual flying exercise. These skills degrade quickly so practical handling and crew procedures should be refreshed regularly.

It is worth noting that much of civil mandated flight training still focuses on technical emergencies. But in the real world of flight operations, accident statistics show that degraded visual environments cause far more mishaps than technical malfunctions. Allocating time and resources to this kind of training should be seen for what it is: a direct investment in safety.

Crew Dynamics and CRM: Turning individuals into a team

The advanced nature of flying techniques in degraded visual environments means that learning to handle brownout is a full crew task. Even in single-pilot operations, task-sharing with crew or ground support can mitigate the challenges. More usually, helicopters carrying out tasks to remote or un-reconnoitred sites are multi-pilot or multi crew.

The importance of an effective crew dynamic and the critical role of con from rear crew using standard callouts was highlighted in the report. Good crew co-ordination provides clarity and predictability and allows Technical Crew to become the ‘eyes’ of the pilots and develop a collectively enhanced situation awareness. This works both ways of course. One technique we used in the military was requiring the flying pilot to state out-loud that he was comfortable with the current trajectory and energy state of the aircraft every couple of seconds throughout the final approach until ground contact. The single word ‘happy’ served this purpose and would reassure the rest of the crew not only that the aircraft was meeting the briefed parameters, but also that the pilot retained sufficient cognitive capacity to remember to say it! If the flying pilot went quiet, it was time to go around. In the dust cloud, workload can rise rapidly and clear, rehearsed communication cuts through the noise.

The Human Factor: The first and last line of defence

Technology may one day give us perfect vision through dust and snow. Until then, or as long as helicopters land on unprepared surfaces, brownout will remain a hazard in rotary-wing operations. Civil pilots cannot avoid it entirely, but they can manage it intelligently. What the 2012 report highlighted was that in spite of all the technological aids out there to enhance flight control and reduce hazards in degraded visual environments, safely overcoming the threat still starts and ends with the crew through thoughtful pre-flight planning, anticipating illusions and threats, selecting and committing to appropriate landing techniques, practicing disciplined crew coordination and communication, and training realistically and often. This is as true today as it was then, and for many civil operators where cutting edge military grade tech is not exactly around the corner, it will continue to be so into the foreseeable future.

Featured image credit: David McNew/Getty Images.