Understanding the impact of helicopter pilot workload during flying emergencies.

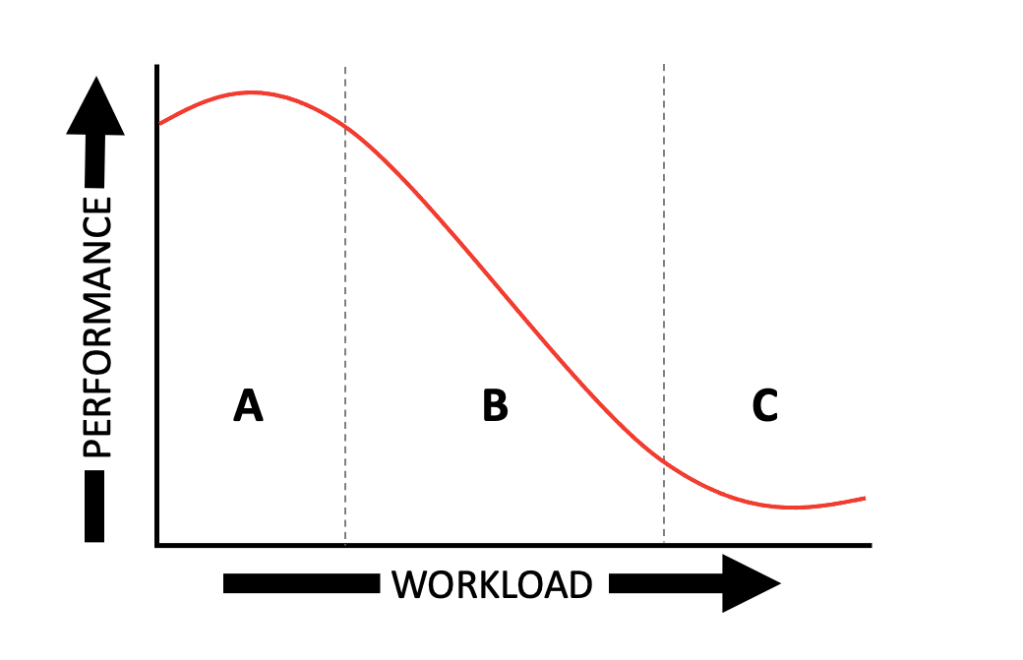

Any conscious mental processing we do that focuses our attention results in cognitive workload. Workload management is about maintaining a balance between level of demand and the mental effort required to meet that demand based on our available resources. Demand can go up, but resource can also go down (think startle, distraction, tunnelling). When demand outstrips resource the outcome is a decline in performance. This is shown in a basic illustration at Figure 1. The red line describes cognitive capacity. In Zone A the pilot has sufficient to maintain performance as task demands begin to increase. In Zone B task demand is such that workload begins to overcome cognitive capacity and performance declines as a consequence. By Zone C, workload has exceeded the pilot’s capacity to such an extent that task performance is almost completely negated.

Figure 1: Relationship between cognitive capacity, workload, and performance.

The problem is how we know when we are approaching zone B. Cognitive workload is an important variable with which to understand pilot performance, particularly in high pressure scenarios, but measuring it is notoriously difficult. A recent study by Brazilian test pilots and academics (Scarpari et al., 2021 ) investigated new methods of measuring it during helicopter emergencies with the aim of better understanding how and when workload makes us hit this downwards performance curve.

Traditional means of measuring workload have predominantly been subjective in nature. Now, technological advances in measuring physiological data using such devices as eye-trackers, electro-dermal activity (EDA), respiratory, heart rate, and blood pressure monitors give real time data during flying tasks and are starting to offer novel insights into how we understand pilot workload, and other complex human factors in aviation. This matters not just in terms of how to operate aircraft safely but also in terms of how we design those aircraft and the systems that a pilot has to interact with.

Cognitive workload is an important variable with which to understand pilot performance, particularly in high pressure scenarios, but measuring it is notoriously difficult.

What is workload?

It is useful to separate the concepts of mental workload and task load which are easily confused. Task load describes the demands placed on us by the quantity or complexity of the tasks we are required to manage. On the other hand, when we talk about mental workload we are describing a cognitive limitation – our human ability to process information. So, task load, for example, might be determined by airspace demands, human-machine interface demands, procedural demands, and the quantity or distribution of concurrent tasks; whereas, a pilots’s cognitive capacity is dependent upon individual differences, including their skills, knowledge and attitudes which determine task familiarity or perceived task difficulty. Obviously, cognitive workload is affected by task load, and time is often the most significant factor of all in provoking a breakdown of cognitive capacity.

Managing cognitive workload

With small variations between individuals, our ability to manage cognitive workload – sometimes referred to in aviation as our ‘capacity’ – is universally limited. It affects all of us and there’s probably no pilot out there who hasn’t explored the limits of their capacity on more than one occasion while at the controls of an aircraft. Sometimes we are hit by a cognitive cliff edge, as might happen, for example, following a startle and surprise reaction or a strong distraction (a fast track to Zone C). Other times we might be conscious of a creeping mental fog or inability to focus (on the slope of Zone B). There are also occasions when cognitive tunnelling or extreme focus is such that we reach our limit without an awareness of it. One of the characteristics of running out of capacity is that it is often pernicious, and easier to recognise in others than it is in ourselves.

With small variations between individuals, our ability to manage cognitive workload is universally limited.

Sometimes, a self-aware pilot who is attentive to the tell-tale signs can recognise the feeling of an encroaching mental dead end. We might have an intuitive notion of how we feel when we have spare mental capacity and when we sense that we have hit its limits, but gaining a scientific understanding of what cognitive workload actually means, how it works, and how it might be measured in practice, is another matter altogether.

The challenges of understanding pilot workload

Traditionally, in areas such as flight test, pilot workload has been measured by using control displacement as a proxy for workload and by evaluating the subjective judgements of the test pilots. Subjective judgement’s might include asking pilots to rate their perception of the workload they experienced on a standardised scale. Subjective workload is important because there is always a difference between the actual level of workload for a task and a person’s perception of how much effort that task might involve. However, more objective measures of workload such as physiological measurements allow us to see responses that even the pilots themselves might be unable to perceive.

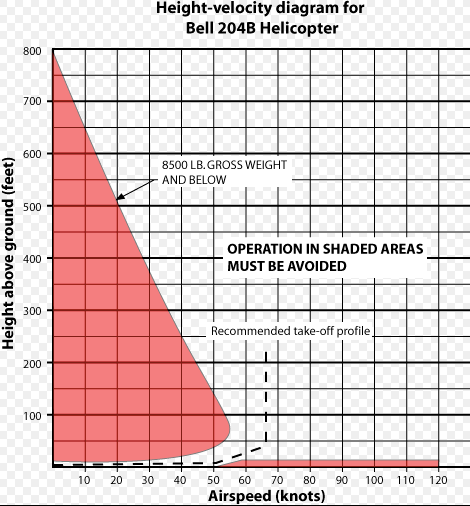

Flight test assessments are used to inform all sorts of important judgments about operational safety from checklist design, to flight profiles and certification standards. One example of this in helicopter flying is the “Dead Man’s Curve”, more officially known as the Height-velocity Diagram’ which describes combinations of height and speed (Figure 2). The diagram shows pilots where successful outcomes following an engine failure are more, or less, likely dependent upon these combinations. Workload is a significant parameter in the construction of the height-speed diagram. As height and speed reduce along the curve of this diagram a pilot needs to make increasingly large and dynamic control inputs to ensure a successful landing. At some point on the diagram the control responses required of an average pilot are determined during testing to be too great, and this is where workload is said to have become too high.

Figure 2: An illustrative Height-Velocity Diagram for the Bell 204 Helicopter

The Brazilian study used the “Dead Man’s Curve” as a means of varying workload and measuring pilot responses from different points on the height-velocity diagram. Each pilot carried out between 12 and 27 autorotations at different height and speed combinations which corresponded to different complexity levels and expected workloads. Measurements were made of vertical and horizontal landing speeds, as well as a range of physiological markers, and pilots’ subjective evaluations of workload.

What did the study find?

The results of this ambitious study showed that continuous measurement of physiological parameters in flight is possible and that these can give useful insights into objective measures of workload. On the other hand, it also demonstrated some of the complexities of usefully measuring physiological markers for such dynamic, short-term, and nuanced cognitive and motor activities. For example, during the test sequences both the electro-dermal activity and heart-rates of the pilots displayed abrupt increases after an engine failure indicating that they do offer good physiological markers. The researchers also discovered a ‘signature’ heart-rate response for each pilot during the different runs which could allow the comparison of individual differences. However, the traces for each pilot did not differ significantly with variations of workload, so heart-rate did not offer a practical method for seeing when pilots’ mental load was greatest. For respiration frequency the results showed an instantaneous reduction instead of the increase which is commonly reported during more prolonged periods of high workload. Both these outcomes show how difficult it is to measure short term physiological responses and suggest that a large and sustained workload difference is needed to translate into significant heart rate or respiration changes as a useful marker for workload.

One of the groups compared in the study contained highly experienced test pilots, all of which had done more than 3000 landings in full autorotation. Despite this, none of the objective workload parameters measured showed a variation according to the experience of the pilots, so there was no evidence that pilot experience had any significant effect on workload.

Perhaps one of the most notable findings of the study was that only two of the pilots had average reactions times that met with those established by certification standards. This is not the first time that a study has called into question the expectation set by certification standards of a one second reaction time in an emergency situation. An extensive study of tail rotor failures in the UK (CAA, 2003) also suggested that certification standards need revisiting to adjust reaction times, perhaps to account for startle and surprise factor.

Conclusion

Learning how to mitigate cognitive overload with good design and human factors measures is increasingly important in a world in which we are adding advanced cockpit systems at an ever increasing pace. A celebrated 2008 study into pilot workload (Casner et al. 2008) found that all pilots (regardless of experience) believe that advanced cockpit systems (such as GPS navigation, autopilots, electronic displays, TCAS etc.) help to enhance their awareness and lower their workload, and they all had a strong preference for using such systems. However, when studied during flight operations no evidence was found that these technological advances actually reduced pilot workload or the incidence of error in the cockpit.

Although all pilots believe that advanced cockpit systems lower their workload there is no evidence that this is the case.

Current methods used to evaluate workload may be imperfect, and building a reliable picture of cognitive workload in action is still extremely difficult to achieve, but assessing it still forms an important part of the design and evaluation of aircraft and systems safety and is part and parcel of the production of flight handling and certification advice. New forms of measuring workload via physiological markers will start to improve our understanding of how and when it impacts performance, allowing us to design better for workload management and mitigate for cognitive breakdowns in critical flight scenarios.

References:

Civil Aviation Authority (2003) Tail Rotor Failures. CAA Paper 2003/1 Available from https://www.caa.co.uk/our-work/publications/documents/content/caa-paper-2003-01/

Casner, S. M. (2009). Perceived vs. measured effects of advanced cockpit systems on pilot workload and error: Are pilots’ beliefs misaligned with reality?. Applied ergonomics, 40(3), 448-456.

Charles, R. L., & Nixon, J. (2019). Measuring mental workload using physiological measures: A systematic review. Applied ergonomics, 74, 221-232.

Scarpari, J. R. S., Ribeiro, M. W., Deolindo, C. S., Aratanha, M. A. A., de Andrade, D., Forster, C. H. Q., … & Annes da Silva, R. G. (2021). Quantitative assessment of pilot-endured workloads during helicopter flying emergencies: an analysis of physiological parameters during an autorotation. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 17734.

One thought on “How do you know when cognitive workload is affecting your performance?”