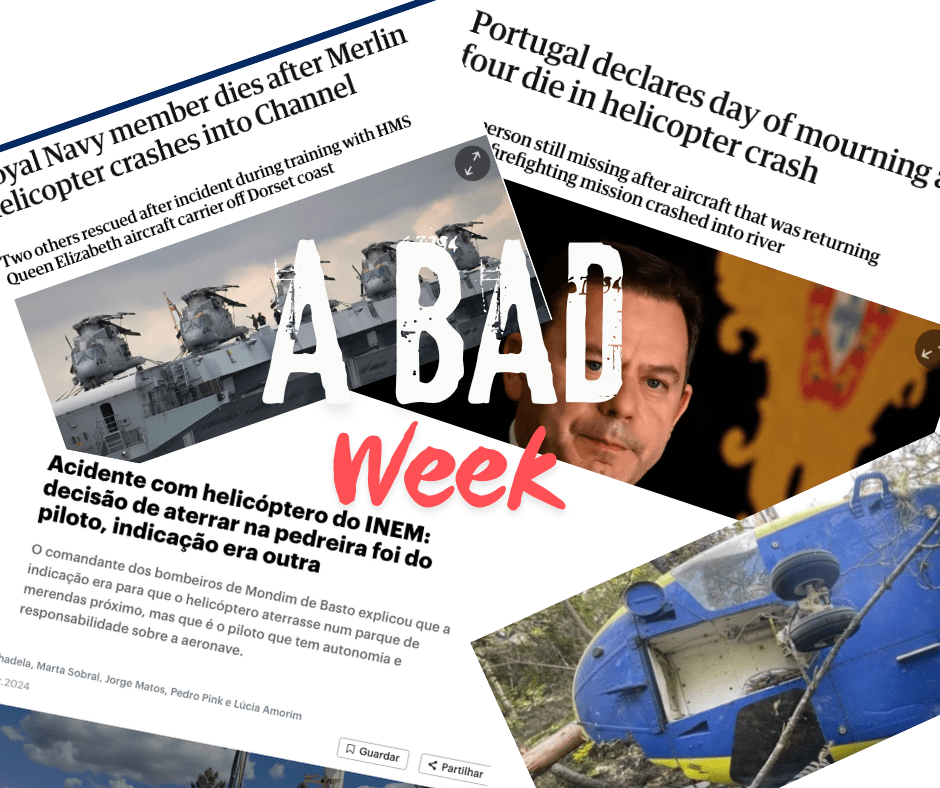

It’s been a been a tough week for helicopter aviation. In Western Europe, three accidents in six days. Six lives lost. More seriously injured. In the rest of the world, another five accidents and over twenty lives. In six days. So many accidents in such a short period of time delivers a strong reminder to us about the kind of tasks that we as a society ask of our helicopters and their crews: They are often difficult, and sometimes dangerous, even for the very best of them.

On 30 August an AS350B3 crashed into a river during firefighting operations in Portugal with a fire team on board. Just three days later, also in Portugal, an AW139 on a HEMS mission crashed on approach to an improvised landing site in brown-out conditions. Only 48 hours after that, a Royal Navy Merlin ditched in the English Channel at night whilst flying from aircraft carrier Queen Elizabeth. As an ex-Royal Navy pilot, ex-employee of another one of the operators, and currently flying on one of the accident aircraft types, for me these feel close to home.

There’s no value in speculating on the causes and contributory factors of the accidents, each which have taken place in very different circumstances. But what they do have in common is that all involved highly trained and professional helicopter crews flying sophisticated aircraft, and each was taking part at the time in three of the most challenging flying operations out there; respectively firefighting, HEMS and night maritime operations.

80% of aviation accidents are caused by human error. It’s an oft quoted figure with some pretty good science behind it, but it can be misleading. Many people draw the beguilingly simple conclusion that if human error is the cause of 80% of aviation accidents, then removing the human should result in an 80% decrease in those accidents1.

Of course, that reasoning is flawed but it’s easy to see how people arrive there. We manage safety in the aviation industry by gathering a whole load of data about what pilots do wrong, and hardly any about what they do right. This is bound to bias our thinking. It led one safety observer to offer the analogy that “In aviation safety, it’s like we’ve been trying to learn about marriage by only studying divorce.“2 As three new accident investigations begin this week, you can be sure that human error will feature heavily both in and outside the cockpit.

It’s easy to focus on what people ‘get wrong’. When an accident happens, attention is immediately and inevitably drawn to the decisions and actions taken – or not taken – by the crew. The armchair critics revel in sharing in their half-baked opinions without understanding the local rationality of the pilots at the time. Looking back, and with the benefit of a YouTube clip, anyone can exercise expert judgement. What exactly the crew knew or didn’t know, saw or didn’t see; what their understanding of the situation in that time and place actually was; what effect goals, external pressures, company culture, and other constraints had on their thinking is 100% opaque to the casual observer.

How many of those same commentators ask to what extent crew actions prevented a worse outcome or on countless other occasions contribute to a safe outcome? How do the humans in the wider system of aviation (controllers, ground crews, maintainers, managers etc.) build resilience into the dangerous activities that we ask of our helicopter teams on a daily basis?

There’s a lot to be learned from studying success. Aviation is full of dynamic change and systemic disturbance, and dealing with unpredictability is still something that lends itself above all to human talents. Pilots perform this adaptive role day in and day out. It has been said that helicopter operations are uniquely challenging in terms of human factors.3 and these challenges are borne out by stubbornly high accident statistics.

Operating helicopters is different to other forms of aviation because a helicopter crew’s main objective is usually to achieve a specific task, rather than simply conduct the flight itself. To do so requires a very different crew dynamic to other types of flying, and highly developed non-technical skills and behaviours. In difficult and often dangerous environments such as the ones these helicopters were operating in, many people don’t realise how just how much and how often that, far from being a threat to safety, a helicopter crew’s role is exceptional and critical in protecting it.

- Kiernan, K. (2019) In Focusing On What Pilots Do Wrong, We May Be Missing Valuable Lessons From What They Quietly Do Right, Forbes Magazine ↩︎

- De Vos, M. Quoted in Ibid ↩︎

- Hart, S. G. (1988). Helicopter human factors. Human factors in aviation, 591-638. ↩︎