Full flight simulators are amazing tools for learning. Training devices have become more and more sophisticated, more and more true to the environment they recreate and, with this innovation, more and more expensive to use as well. But have these advances made them more effective as training tools in parallel, or is there a limit to the benefits of ever-increasing realism to the learning environment? This article aims to explain two of the key concepts in using simulated environments for training, fidelity and transfer of training, and invites you to consider the pros and cons of your own experiences of teaching and learning in the simulator.

Almost from the dawn of flight, those pioneering the discipline of flying instruction soon realised the value that devices recreating the cockpit environment would bring to pilot training. In 1910, one of them, D.M. Hayward, opined that “the invention of a device which will enable the novice to obtain a clear conception of the workings of the controls of an aeroplane, and of conditions existent in the air, without the risk personally or otherwise, is to be welcomed without a doubt.”

So safety was the initial catalyst for the development of flight training devices, and remains a key reason for flight simulation today. However, a safe environment isn’t the only advantage to using simulation for flight training. And while many of the advantages are straightforward and obvious, the limitations of using simulation – being human centric – tend to be much more complex and nuanced. These limitations are principally associated with ‘fidelity’, a term which invites us down a rabbit hole of psychology and human performance and branches off into sub-categories and further terms that need to be explored. Fidelity is born of the notion that no simulator is a 100% match for the real world.

Advantages of training for flight using a simulator.

First the easy bit. A simple list should suffice for a summary of the advantages of flight simulators:

- Increased safety. Pilots can drill their responses to tasks too dangerous to carry out in live training. Non-normal and emergency procedures, fires, you name it.

- Lower training costs. For wide bodied airlines the cost per hour of using a simulator compared to the real aircraft is somewhere in the ballpark of 25 times cheaper. It also leaves more aircraft available for generating revenue from line flying.

- Resource availability. The simulator is not affected by seasonal, environmental or operational restraints (think weather minima or air traffic delays). Day or night flight can take place 24-7. Almost any simulated airfield can be made available at any time.

- Instructional facilities. Trainers can pause, fast-forward, replay, relocate and review. All this has a huge impact on training efficiency, and gives access to a much richer range of instructional strategies. For example, task load can be increased or decreased depending on how a student pilot is coping with the scenario.

- Reduced environmental impact. Less flying equals less emissions. Less resources spent. Less noise pollution. Simple.

The limitations: How effectively does training in a simulator transfer to real situations in real aircraft?

What about the limitations of flight simulation? The main concern of using simulators to train is how well the training delivered in a simulator transfers to a pilot’s behaviour in the real world. Known simply as ‘Transfer of Training’, this problem is inseparably coupled to the concept of fidelity.

Transfer of training is inseparably coupled to the concept of fidelity.

What is simulator fidelity? Understanding different types of fidelity.

Physical and Functional Fidelity

When most people think of fidelity they tend to think about how much a simulator looks like the real aircraft. Here’s a picture of a very early (1920-30s era) simulator known as the Link Trainer1.

Figure 1

It looks a little bit like something from a fairground, or one of those musical rides for kids that sit out the front of supermarkets or shopping malls. Despite the evident fidelity gap between the Link Trainer and the hi-tech simulators we know today, its mechanical control actuation, magnetic compass, and functional flight instruments, nevertheless represented the cutting edge of flight simulation about one hundred years ago.

Even back then, the inclusion of real flight instruments and controls reflected a popular idea that the closer the simulated aircraft is to the real aircraft the better. This is physical fidelity: the degree which the layout and the components of the replicated environment mirror the real one. In modern simulators physical fidelity can itself encompass multiple characteristics including visual fidelity (does it look like the actual environment?); aural fidelity (does it sound like the actual environment?); haptic fidelity (does it feel like the actual environment?); and vestibular fidelity (does it create the same sense of movement as the actual environment?).

Functional fidelity (also sometimes called model fidelity) refers to how accurately the control response and the characteristics of the flight model mirrors those of the real aircraft, including systems functionality, and ergonomics such as switch selections. Functional fidelity also covers environmental effects such as terrain, weather, wind, or turbulence.

In helicopters especially, in some phases of flight, functional fidelity can really matter. For helicopter pilots, some manoeuvres such as hover tasks and autorotation require an intimate familiarity with the flight dynamics and handling qualities of the aircraft being flown. Learning from a simulator model combines the acquisition of rule-based and skill based behaviours which demand high accuracy models and high fidelity simulation. Most helicopter pilots would agree that there is still a significant fidelity gap between simulator and in-flight training in certain areas such as these.

Both physical and functional fidelity represent the ‘easy to grasp’ part of the fidelity equation. This is because they can be objectively measured and agreed upon. We can all easily conclude that Image A has a lower level of physical fidelity than Image B.2

Figure 2

For the past one hundred years as flight simulation steadily developed and improved into full sound and motion all-axes platforms it has been taken as axiom that the closer a simulated environment is to the real thing, the higher the level of training effectiveness. In other words greater fidelity equals greater transfer of training. However, the relationship between improved training and improved physical fidelity in a simulated environment is far from linear, and we will explore why in more detail in a moment. In reality, when it comes to training effectiveness, what we are really interested in is psychological or behavioural fidelity.

Behavioural/psychological fidelity

The focus on physical fidelity neglects what is probably the most important aspect of training transfer, which is actually the effective transfer of pilot behaviour to the real aircraft. Behavioural fidelity is about the extent to which a simulated environment recreates the same behavioural responses in pilots that they would have for real. We are talking about the replication of factors such as decision-making, workload, situation awareness, communication, and crew interaction.

Psychological fidelity is defined as the degree to which a simulation causes the subject to respond psychologically in the same ways that they would for real. One of the oft-discussed topics in this regard is the effect on pilot behaviour caused by the psychological gap between the inherently safe environment of a simulator and the jeopardy of a true flight environment. Does a complex or challenging emergency in the simulator provoke the surprise or the same stress response as it would in flight? Linked to this is the idea of ‘motivational fidelity’ which describes the degree to which a training device engages the user when using it. This in turn is related to the term ‘immersion’. True immersion is felt when there is no conscious distinction made in the experience of the subject between the simulated environment and that of the real world.

All of these psychological elements affect pilot behaviours. And remember that any difference between how pilots behave in the simulator and what they would do in the real aircraft is potentially problematic. Consequently, most of the limitations that we associate with the use of flight simulators are better understood in terms of behavioural fidelity.

Most of the limitations of flight simulators should be understood in terms of behavioural fidelity.

How does fidelity affect training quality?

Traditional learning theory (Thorndike, 1903) holds that the closer a simulated environment is to the real thing, the higher the level of training effectiveness. That is to say, that in pilot training “The closer a flight simulator corresponds to the actual flight environment, the more skills will transfer to the aircraft” (Klauer, 1997). This theory has underpinned years of development and innovation in simulator training. It is an intuitive and persuasive assumption to believe that the closer the simulator replicates our real, operational flight environment, the closer our behaviours will approximate real behaviours in flight. (i.e. greater physical and functional fidelity = greater behavioural fidelity). But it is not quite so simple as to say “greater fidelity equals better training.”

There is also research that shows that only a certain, limited set of properties are needed to support transfer of training, and other elements need not always be represented accurately. Alessi (1988) argued that there is not a linear relationship between learning and fidelity because high fidelity usually also means high complexity. Higher complexity requires a corresponding increase in cognitive effort and increased workload on the part of the trainee. The ability to benefit from a high level of fidelity depends upon factors such as the technical knowledge, expertise and experience level of the learner in question. Cognitive Load Theory (Wickens et al. 2013) provides an intuitive counterpoint to the argument for ever greater fidelity. It predicts that if you lower the cognitive load of a task during training, then more cognitive resources are available to facilitate absorption and learning of that task. This is why, in early stages of training, tasks for learners are simplified or broken up into their constituent parts, a concept any flight instructor is familiar with.

Where fidelity meets transfer.

Bearing all of that in mind, and now that we have an understanding of fidelity we can pose and try to answer some important questions.

1. What is the ‘optimal point’ beyond which an increase in fidelity actually results in a diminished degree of transfer of skills for some pilots?

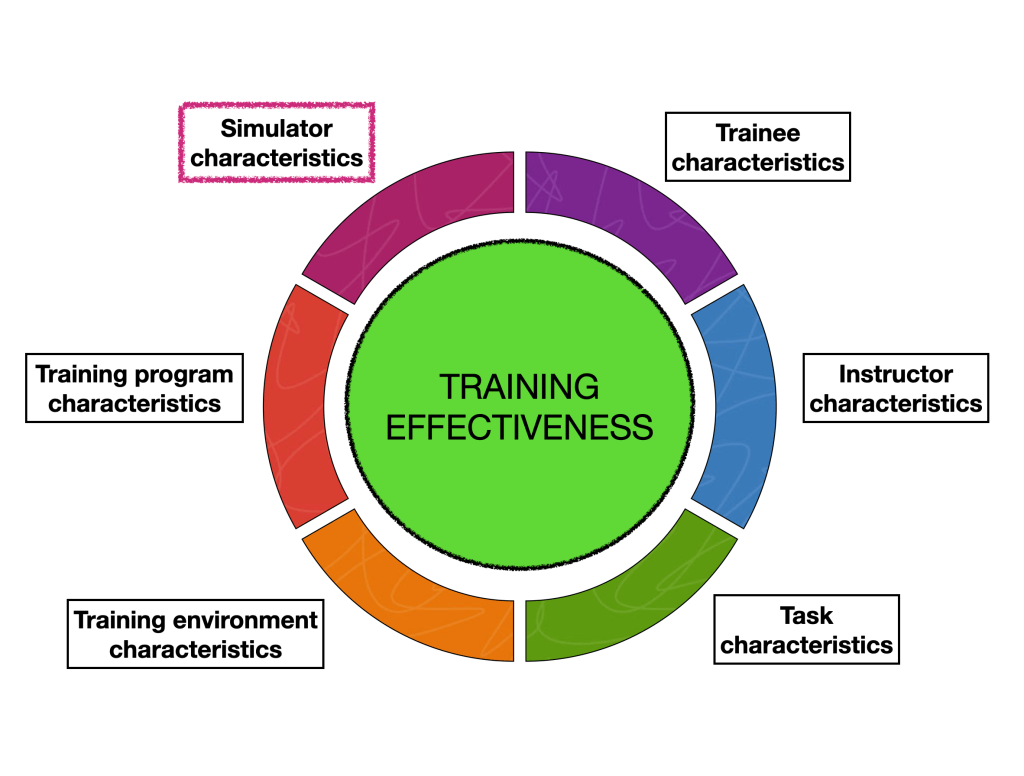

In complex systems such as a modern flight deck, too much physical fidelity and functional fidelity could impede learning. Finding the optimal balance of fidelity versus transfer of training is complex because it depends upon all of the other factors in the training equation (see Figure 3). Consider the difference of approach required for expert pilots versus novice pilots. Highly expensive full-motion simulators are fantastic tools for some individuals and for some areas of training, but their use is not always appropriate to trainee learning. The characteristics of a simulator represent only one element contributing to training effectiveness, as can be seen in figure 3. Its significance depends upon the relative size of the other parts that close the circle. The optimal fidelity for transfer of training is therefore not about the simulator at all, but is driven by individual differences in pilot competency and experience, and is dependent upon good training programme design. These need balancing by a training organisation to match level of simulation to the type and nature of training needed for the pilot in question. Horses for courses.

Figure 3

Factors affecting the effectiveness of simulator training.

In actual fact, transfer of training is more dependent upon good training design than it is upon the physical fidelity of the equipment.

2. How do we know we are transferring the behaviours we want to?

It is important that simulator training does not provoke the transfer of negative pilot behaviours learned from slight inaccuracies in the model, or from a gap between learned actions and reactions in the simulator and those desired in the real aircraft. Negative transfer can be a problem. For example, several accidents following helicopter engine failures have been linked to pilots failing to perform an effective autorotation owing to deficiencies in the way the manoeuvre is practiced. One of the challenges of monitoring behavioural transfer for negative effects is that they cannot be assessed until after a simulator has been designed and certified. In many cases however, these incidents are not always just a question of a fidelity gap, but encompass other factors driving behavioural transfer from training, such as instructional technique or problems in training design.

3. Does performance in the simulator translate to performance at the same task in a real aircraft?

Conclusion

Does performance in the simulator translate to performance in the aircraft? It should do provided we get behavioural fidelity right. If the level of physical and functional fidelity provided in training (however low it may be) is capable of generating pilot behaviours that are true to their real flight environment, then performance will transfer. Understanding what level that may be for each individual is the challenge because it will change according to a trainee’s needs, experience, and the nature of the task in question.

There is a strongly held misconception within the industry from regulators to student pilots that the higher the level of fidelity, the better the transfer of training. Though it’s appearance might be deemed almost laughable by today’s standards, in the 1930s the early adopters of the Link Trainer obviously believed that their model had sufficient realism to train pilot behaviours effectively for real flight. The lesson? Despite our perception that more is better, perfect physical and functional fidelity are not actually required to achieve transfer of training. Perhaps this is lost on us in the era of burgeoning virtual reality and immersive training concepts ?

References:

Scaramuzzino, P.F. (2022). Flight simulator Transfer of Training Effectiveness in Helicopter Manoeuvring Flight. [Dissertation (TU Delft), Delft University of Technology]. https://repository.tudelft.nl/record/uuid:40a2113a-98c9-4ec1-a2b7-5f6c003caf84

- There is an original Link Trainer in the lobby of the Finnair Academy in Helsinki for any interested pilots who might find themselves up north. ↩︎

- Furthermore, the difference between them is fairly easy to measure. Even today, the regulations which underpin the certification of full flight simulators are based on this assumption. This is why when aviation authorities certify flight training devices they primarily assess physical and functional fidelity. ↩︎

One thought on “Getting the right amount of stimulation from your simulation: What role does fidelity have in training to fly? ”