What is cultural competency?

Just mentioning the word culture seems often to be met with a glazing over of eyes. I learned that discussing ‘cultural capability’ in the military was unfashionable, uncool, and frankly unmilitary: making the case for so called ‘soft’ skills doesn’t sit well with the hard and pointy image of waging warfare. I have a sense that the same is true in the world of aviation, which is ironic given the uniquely international nature of the industry.

What is cultural competency? From 2012-13 I spent many hours of my time pondering this question whilst sat alone in a dusty tent in Camp Bastion, the UK’s main military stronghold in Afghanistan. My ‘day-job’ – although mostly by night – was flying a military helicopter out over the southern Afghan desert. By day, when I wasn’t sleeping, I was in the throes of finishing a thesis on the UK military’s cultural capability. It was the final task to achieve a masters degree in International Liaison and Communication. Just as Afghanistan itself would teach the Western military nations deployed there over many years, the enduring lesson I learned from that period of study was just how complex and convoluted culture is both as a concept and in practice. And, that if you choose to ignore it you do so at a cost.

Defining culture

Culture is like a river: its characteristics are constantly changing. Some quickly and some more slowly.

Whilst acknowledging the risk of glazed eyes after scarcely a paragraph, any discussion of culture usually has to begin with the process of defining exactly what we are talking about. Most explanations of culture are necessarily limited, partial, bounded, and often require a liberal use of analogy to help people make sense of its complexity. This will be no different. One of the best analogies I have heard is that trying to define culture is like trying to define a river. Take a moment to try and define a river. Is it long or short, winding or steep? You can describe a single point on a river by focusing on any number of different characteristics: breadth, depth, speed, temperature, colour of the water, currents in the water, life supported by the water, and so on, and so on. But is it possible to describe it as a complete entity? The characteristics of the point that you choose are themselves changing with time. In times of flood the water flows faster, in winter it flows colder. Pollute it and it will change colour, acidity, oxygen level, and support less life. It is just the same with culture. Like a river, a culture can never stand still. Its characteristics are constantly changing, some quickly and some more slowly.

Breaking down our cultural make-up

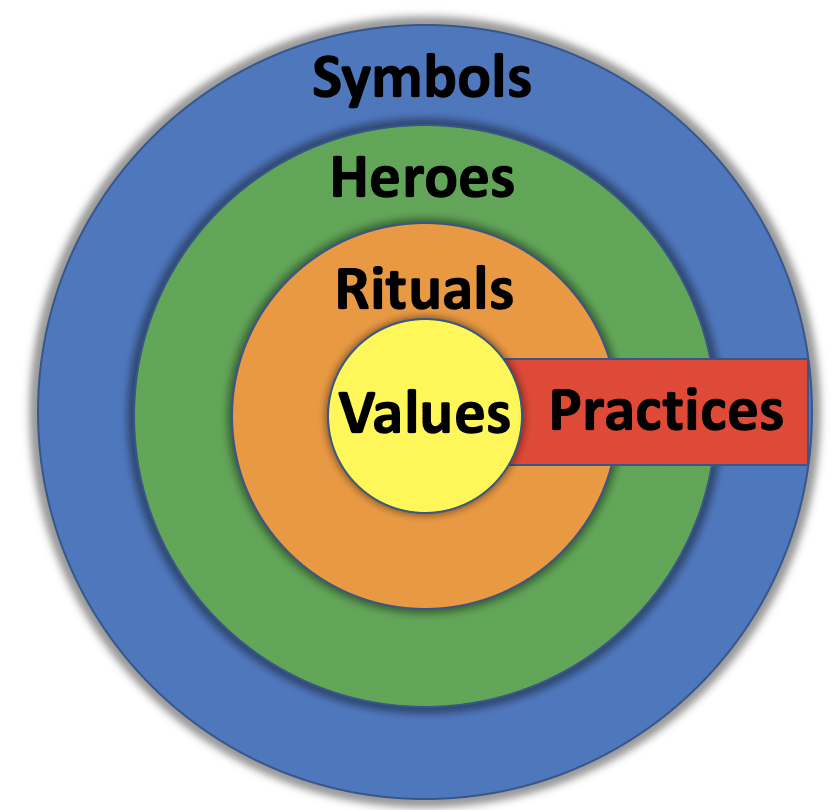

Culture is not something that we inherit, but is a mixture of traits and behaviours which are learned from a very early age from the social environment in which we are immersed. The culturally driven elements of your character manifest themselves in several ways, and how deeply rooted inside you these characteristics are is often likened to the layers of an onion.

Values

At the deepest level the environment in which we are brought up forms our values. You can think of this as your cultural core. It is what determines the way we think about the world around us and what matters to us. Our values are our preferences for certain states of affairs over others, and psychologists believe that these are mostly entrenched in us by the age of ten. For example, our openness to change and unpredictability, our desire to submit to hierarchical control or enjoy freedom of action, or the importance we place on independent living or the value of family groups.

In the workplace we will have different beliefs about the importance of professional advancement over the maintenance of good working relationships; the correct balance between work and home life; and the value of job security over challenging and stimulating work. All of this depends on how and where we were brought up.

Rituals.

Rituals are elements of a culture considered to have an essential social function. Culture is a collective concept. It is always about people in groups. At a macro level our social, religious, and political ceremonies and institutions are an example of rituals, but similar rituals are evident at all levels of culture. If we look at the occupational culture of aviation some examples include the awarding of wings at the end of training, the celebration of milestones such as hours totals, or the water cannon salute that meets a captain at the end of a long career.

Heroes.

Heroes are figures (alive, dead, real or imaginary) who possess the characteristics highly prized by a given culture. To the members of that culture they serve as models for behaviour. Aviation is a good example of a culture that puts a huge emphasis on its heroes. From the Wright Brothers to Captain Sully of Miracle on the Hudson fame we don’t have to look far to find tales and characters from aviation derring do and recognise the function they have for our self-image as aviators.

Symbols

Symbols are words, gestures, pictures or objects that hold a particular meaning recognised by those who share the culture in question. This is the most superficial layer of culture, but also the most visible. Symbols are also very important and evident in the culture of aviation. A whole aeronautical language exists thick with jargon that is in many ways exclusive to those not imbued with years of training. Badges, flags, aircraft livery, wings on chests and stripes on shoulders; symbols abound. Often aircraft themselves serve as status symbols and objects of professional pride.

Distinguishing between national and organisational cultures

Why explain the constituent elements of culture in such detail? Because each has a different role in cross-cultural interaction. Rituals, heroes, and symbols together make up the practices of a culture. They are the parts of a culture that are visible to the outside observer. Practices form the parts of other cultures that we might stereotype and poke fun at, but it is values – the core – (which remains mostly hidden below the surface) that are most significant in inter-cultural communication.

National cultures

It should come as no surprise that studies have found considerable differences in values between national cultures. Values within groups are extremely stable traits and have largely remained unchanged over hundreds of years. Our values determine who we are and how we think. They are the deeply rooted elements that have been cultivated in us since childhood, and therefore they are intrinsically tied to our nationality – where and how we have been brought up. It follows then that values are most identifiable at the level of national cultures.

Organisational cultures

If cultural differences between nationalities are more about values and less about practices, when we examine organisational cultures we find the opposite is true. Cultural differences in organisations are more about practices, and less about values. An organisational culture is a different beast altogether from national culture, not least because members can choose to join it, are not entirely immersed in it, and are likely to leave it again at some point in the future.

When senior management in an organisation think culture, they tend to talk about their vision of company ‘corporate’ culture, not the deeper cultural make-up of their teams. But, compared to national culture, the impact of corporate culture on an individual or group is much more superficial than bosses might like to imagine. Instead of focusing on organisational culture, managers would do well to pay a bit more attention to the cultural dynamic between nationalities in their workforce. They often chronically underestimate how culturally-fed misunderstandings can impact decision-making processes, output, and relationships within their business.

Working in a multi-cultural team

Aviation gives its workforce a potentially unparalleled opportunity to experience the culturally enriching environment of multinational teams. It is often a melting pot with most medium to large companies being a mixture of employees from more than one, and often many, national cultures. Numerous studies have shown the impact national culture can have on such organisations and the role cultural competency (or incompetency) has on team dynamics is profound.

I have been lucky to have had many opportunities in my career to work cross-culturally and I have always enjoyed doing so. When my latest career step offered me the opportunity to live and work in the Caribbean I couldn’t have imagined quite what a multi-cultural and multi-lingual world I would be stepping into. Moving from Spain where I had been living and flying for the previous four years, I soon found myself on a tropical island where most people switch comfortably between four languages. Speaking only two puts you somewhere towards the bottom of the class. I joined a small team of around 25 aircrew and engineers made up of personnel from no less than nine different nationalities.

My previous (and current) experience has reinforced (and continues to provide evidence for) something that first came to my attention while studying the lessons learned by the military in Afghanistan:

cultural competence is not something that is given much thought by…well, almost anyone!

Neither the individuals that make up these organisations, nor the organisations themselves tend to stop to consider the role of intercultural dynamics. Much less do those in charge consider that these are worth investing any time or resource. This is a shame, because as we will see, achieving a basic level of cultural competence takes very little education, even less training, and (at its most basic) requires little more than simple self-awareness.

The impact of national cultures on organisational cultures

The fact that organisational cultures are relatively superficial and value free is precisely the reasons why international organisations can exist and be composed of people of different nationalities, each with their different national values. However, it follows that the cause of any deeply felt cultural misunderstandings within an organisation are usually rooted in value-differences, for which we must look to each other’s cultural inheritance to unravel.

Within multinational teams, questions of economic, procedural, technological, or group cooperation are too often considered to be technical rather than cultural problems, when it is actually differences in thinking among the participants which explain why solutions do not work, or fail to be implemented. Understanding such differences is at least as essential as understanding the technical factors. Confrontations, of greater or lesser degree, between people and groups who think, feel, and act differently is inevitable in any organisation with a culturally diverse workforce. Such confrontations do not necessarily depend upon the absolute values of a person’s culture, but rather their relative values compared with somebody else’s.

Developing cultural competency

There is no normal when it comes to culture.

There is no normal when it comes to culture other than what is normal to us as individuals. We are the normal ones. Everyone else is odd and their habits are strange. We recognise the differences of people from other cultures all around us. But while it is easy to see cultural difference in everybody else, we tend to neglect to examine our own cultural inheritance. The first step on the road to cultural competency is actually very easy. It is no more than a simple awareness of the constraints of our own way of thinking. Consciousness of the limitations of our own value system changes how we see the values of others and helps draw us towards common ground.

Another well known anecdote about the limiting impact of culture on us as individuals describes a wise old fish in a river who in passing a shoal of young fish throws out a friendly hello.

“Hi there, young friends, how’s the water this fine morning?!”

The young fish shoot each other confused glances. Then, when Old Scaley has swum well past they ask each other,

“What the hell is water?”

The basic skill for surviving in a multicultural world, is understanding one’s own cultural values

The same is of course true for us. When you are immersed in a culture it is almost impossible to perceive that culture and recognise its characteristics. People who have only ever lived in one culture can see regional and individual differences but find it hard to discern their own national culture and are usually unable to describe it other than in terms described to them by outsiders.

So finally we return to the question posed at the start. What is cultural competency? Counterintuitively perhaps, cultural competency begins by looking inwards not outwards. It is more about being able to identify your own cultural baggage and idiosyncrasies than it is about being able to see differences in others. Geert Hofstede, one of the world’s leading scholars on the subject of culture explains that, “the basic skill for surviving in a multicultural world, is understanding first one’s own cultural values.” Only then need we turn to the cultural values of the others with whom we have to co-operate.

Counterintuitively, cultural competency begins by looking inwards not outward

One thought on “Navigating cross-cultural turbulence: Why the multi-national complexion of aviation demands we should all add culture to our competencies.”