Prologue

A seriously injured sailor lay crying in agony after falling down a deck hatch. Suffering from severe concussion, and multiple fractures, he lay awkwardly, deep inside his boat, wedged between engine and fishing machinery. It was the job of the helicopter rescue swimmer to work out how to remove him to a place of safety. Stretcher and casualty were too large to fit back up through the hatch, but they would fit through a hole in the side of the boat designed for fishing nets and equipment. The swimmer quickly formulated a plan to climb outboard and hang over the boat’s side while anchoring himself to a hard point on the inside, allowing manipulation of the stretcher into a safe position from which it could be winched on board the helicopter. “I solved it as best I could, but it was a complicated one”, he explained afterwards. “[In search and rescue] we need to be creative… use all the assets that you have. Not only our equipment… also anything that you can use on the deck, or people who can help you. You carry so many tools in your bag, and you use them when you need them, all the time selecting, choosing tools for the task. For this mission, it worked.” (Pastor, J. cited in Quinn, J., 2022).

Summary of a study into helicopter non-technical skills

This summary is based on a research project that was carried out by the author as part of the requirement for the award of an MSc in Human Factors in Aviation. It explains the aims of the study, key findings, and conclusions about the significance of operational unpredictability and operational variability on non-technical skills use in the helicopter sector.

Study Title

Ready for anything? Non-technical skills in helicopter operations: Is there a relationship between mission unpredictability and cognitive readiness?

What is Cognitive Readiness?

Theorists have identified a specific group of non-technical skills which they suggest can be used to predict how well we can apply brain and think effectively in complex, dynamic and resource-limited environments.

Put simply in the context of operating helicopters then, Cognitive Readiness describes the cognitive potential of a crew member to perform effectively in complex and unpredictable flight operations.

The purpose of identifying and grouping these non-technical skills is:

1. To consider the cognitive response to uncertainty, complexity, and dynamic change.

2. To predict cognitive performance.

Note that Cognitive Readiness is not something we possess inherently but is situational: it depends upon the individual’s circumstances and the specific situation that they are facing at any given time.

Descriptions of Cognitive readiness were first driven by military funded research into how to prepare personnel for the mental flexibility demanded of military (particularly combat) operations. However, it has since been effectively argued that the concept can apply to any task which is cognitively demanding, unpredictable, and involving a potentially high level of complexity.

Aviation as a socio-technical system contains all these traits, and flying operations often present uncertainties which impose high cognitive and perceptual loads on crews. Aviation is also a frequently time-constrained environment, time being another important factor impacting cognitive load. On top of this, reactive helicopter operations – those which respond to emergency, or other high priority ad hoc tasking – further amplify these factors.

Rationale

The study aimed to determine whether the concept of Cognitive Readiness is applicable in the context of helicopter operations and whether it could be a useful construct in describing and training how helicopter crews use non-technical skills.

The specific research objectives were:

1) To investigate whether helicopter crews’ descriptions of their task environment conform to definitions of cognitive readiness.

2) To determine whether crews recognise component attributes of cognitive readiness as a skillset they employ.

3) To establish whether there is a relationship between the unpredictability of an operation and the use of non-technical skills behaviours associated with cognitive readiness.

4) To determine whether there is a significant difference in the reporting of cognitive readiness knowledge, skills, and attitudes between reactive and non-reactive operations.

Background to the study

The activities and operational environment of helicopters are uniquely challenging in terms of human factors. Although the need for aircrews to adapt to changing circumstances is common to most sectors of aviation, it is especially salient in the world of helicopter critical missions which combine the demands of aviation with those of emergency response. These are high-risk operations with little room for error, and, consequently, have higher accident rates than other areas of commercial aviation. Two examples of these operational tasks are the Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) and aerial firefighting sectors. In the case of the former, EASA (2019) recently announced its intention to draft new rules in response to persistently high accident rates in HEMS, acknowledging its ‘uniquely hazardous’ nature, owing to time pressures, planning challenges and environmental factors. In the latter, the scale and scope of firefighting operations worldwide is increasing rapidly and is even more hazardous. A report from the Australian Transport Safety Board (ATSB, 2022) investigating occurrence statistics in aerial firefighting from 2000-2020 shows a significant upward trend in accident rates. In July and August 2020 alone, three helicopters and three air tankers crashed, causing the deaths of six aerial firefighting professionals.

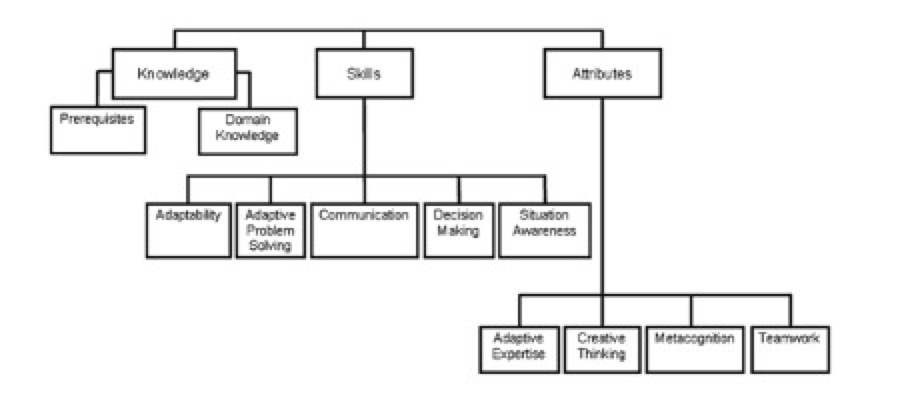

The diversity of helicopter tasking, the breadth of rotary wing flight profiles, and the large proportion of reactive emergency missions they carry out mean rotary wing operations are often characterised by a high-level of unpredictability. Crews’ ability to perform effectively in this kind of task environment depends upon their non-technical skills. Indeed, estimations consistently suggest that human factors rather than technical failures are behind 70-80% of aviation occurrences (Wiegmann & Shappel, 2001).Cognitive readiness describes a set of non-technical skills specifically identified by researchers to be those elements which determine and effective cognitive response to conditions of unpredictability and changing circumstance. The model below shows the make up of these knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Cognitive Readiness Model of O’Neil et al. (2014) based on Knowledge/Skills/Attributes.

The Research

A survey was distributed to helicopter crews worldwide. A total of 584 were completed. Participants represented a cross-sectional sample of the global helicopter industry composed of crews from a wide variety of operational tasks. Demographic information was used to break the sample down into groups by operational task, including Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) (n= 107), Military (n= 129), Police (n= 57), Search and Rescue (SAR) (n= 185) and Firefighting (n=28), and crews from a mixture of other non-reactive operations such as commercial transport (CAT), training, and other professional aerial tasks (n= 79). The purpose of the survey was to compare the perceptions of operational unpredictability and the attitudes associated with cognitive readiness reported by crews across different mission types.

Results

Operational unpredictability in helicopter operations

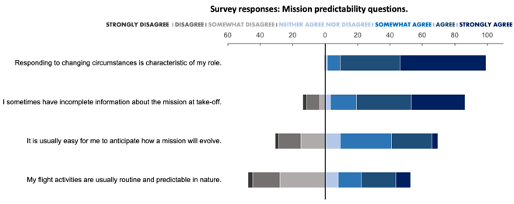

The survey responses showed that reported levels of unpredictability were generally high across operational types. 99% of respondents agreed that changing circumstances were characteristic of their role, with over half strongly agreeing with this statement. During a mission, 70% said that they found circumstances could change significantly on at least a regular basis, with 48% saying this happened frequently or very frequently in their operation. The most highly reported reason for this was a significant change to environmental or meteorological conditions, such as a task extending from day to night or the need to switch from visual to instrument flying due to deteriorating conditions.

Changes in task objective

Over a third of crews also reported changes at least regularly, or more frequently, to their task objective (for example, having to prioritise one of several simultaneous rescues, or being re-tasked or stood-down from a task in flight); point of landing (for example a change in destination hospital depending upon the nature of a casualty’s injuries); tasking information (such as the number of casualties or the advance of a fire front); and payload (for example, the requirement to board additional passengers).

Changing circumstances

Many other types of changing circumstances were cited. Some of these were universal across operational activities, including, for example, the impact of changes to ground support services, aircraft serviceability/equipment failures, and flight time limitations. Others were specific to operational activity, such as a changing threat environment or changes in tactical communications codes (military) or a moving point of departure/arrival (maritime).

Incomplete tasking information

83% of crews reported that they sometimes have incomplete information about the coming mission. At the point of take-off, over a quarter of helicopter crews reported still lacking information about the objective of their task at least regularly. Over half said they regularly to very frequently lacked an accurate task location or duration and nearly a third of respondents said they lacked information about an incident or a casualty frequently or very frequently.

Differences between operations

Analysis of differences between the groups (HEMS/SAR/Firefighting/Police/Military/CAT) demonstrated a significant difference in the level of unpredictability reported according to operational type. As was hypothesised, the results showed a particularly large difference in unpredictability between non-reactive flying tasks (e.g. Commercial Air Transport) and reactive (emergency response) groups. Of all the groups police aircrews reported their operation to be the most susceptible to changes in task objective, changing circumstances, and operational unpredictability.

Crew reporting of cognitive readiness attitudes

The second research objective was to determine whether crews recognise component attributes of cognitive readiness as a skillset they employ in their task environment. 85% of participants responded that they strongly agreed, agreed, or somewhat agreed with statements describing the use of, or recognition of, cognitive readiness attitudes and behaviours.

The relationship between mission unpredictability and cognitive readiness.

A correlation analysis was made to determine the relationship between the level of operational unpredictability reported by different groups and the level or recognition that each of these groups had for the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that determine cognitive readiness. The results showed a significant positive relationship between the two variables. That is to say that the greater the perceived unpredictability of an operation, the more crews identified with the attributes described by cognitive readiness.

Conclusions

Operational Unpredictability

The range of operational tasks performed by helicopters is broad, and the skillsets required are varied. Although the survey results revealed that some of the variables which contribute to task unpredictability are universal to the aviation environment (for example, weather, aircraft malfunction, and air traffic factors), they also showed that some operational tasks clearly encompass a higher level of unpredictability and dynamic change than others. Many factors that introduce unpredictability to a task are a function of the type of operational activity, with Police and HEMS aircrew reporting the highest levels of unpredictability.

It should perhaps come as no surprise that reactive operations, which involve an emergency response to developing situations, report a higher level of unpredictability in general, less information about their task prior to departure, and more frequent changes in mission circumstances once airborne. However, notwithstanding their potential for periods of unpredictability, even emergency services work can include routine and boredom, something evident from responses to the question “my flight activities are usually routine and predictable in nature,” where over fifty per cent of participants agreed to some level. For example, search and rescue flying involves a high proportion of training hours to maintain different skillsets, which means that while operational tasking might be highly unpredictable and changeable, there is also routine and repetition in much of the day-to-day flying schedule.

One of the most interesting results came from the military aircrew group, which reported a notably lower level of unpredictability in their operational tasks than groups dedicated to reactive tasking. This probably reflects the fact that they operate a much broader range of flying tasks than dedicated emergency services assets such as police, SAR, HEMS and firefighting aircraft, some of which are likely to involve much more routine and planned flying.

Data from the military was excluded from both reactive and non-reactive groups as it did not fit satisfactorily into either one. This result is of particular interest because of the military provenance of cognitive readiness which was posited to apply first and foremost to the characteristics and challenges of military operations. Cognitive readiness research has remained heavily defence-oriented despite its relevance beyond the military being highlighted almost from the outset; however, military helicopter crews reported a significantly lower operational unpredictability level than emergency services aircrew. This finding further supports the validity of cognitive readiness to fields other than the military such as aviation and suggests that there are other task environments where its concepts could be even more relevant and applicable than it is to military operations.

Cognitive Readiness

The survey revealed a high level of recognition of all the cognitive readiness components probed in the questionnaire by helicopter aircrew, regardless of mission type. The level of familiarity of aircrews with the terminology and significance of non-technical skills from their everyday flying activities is unusual, if not unique, as a group of professionals, and is likely to have contributed to their recognition of these traits and behaviours. It is reasonable to suggest that regular, dedicated Crew Resource Management (CRM) training, the overt discussion of competencies such as problem-solving and decision-making, and the established practice of reflective debriefing of both technical and non-technical learning points means that many of the Knowledge/Skills/Attitudes of the cognitive readiness model are already built-in to the culture of professional flying.

Police crews reported the highest level of cognitive readiness attitudes, a finding that is consistent with the high level of unpredictability reported in their operation. On the other hand, military crews reported the second highest level of cognitive readiness attitudes, which was at odds with lower levels of unpredictability reported in military flying. Identification with these attitudes could be a product of a strong organisational culture in the military that nurtures a narrative of adaptability and responsiveness to change both inside and outside the sub-culture of military aviation. Oprins et al. (2018) found that military personnel estimate their adaptability competency higher than civilians do, and adaptability and adaptive expertise were elements of the survey given particular attention for their relevance to cognitive readiness.

The relationship between operational unpredictability and cognitive readiness

The main finding of this study was a significant positive correlation (r = .31) across the whole sample between operational unpredictability and the recognition of components of cognitive readiness. This suggests that crews develop these cognitive readiness knowledge, skills, and attitudes in response to the challenges of complex, uncertain and fast-changing task environments and because of experience gained from these challenges. The more unpredictable the flying task, the more evidence there is of cognitive readiness competencies.

The results also suggest it is reasonable to conclude that at the level of individual operations, there is a link between the unpredictability of a given activity and variations in how cognitive readiness competencies are employed by helicopter aircrew. The more unpredictable the type of operation, the more evidence there is of the use of these competencies by aircrew. This link in helicopter missions was established by Hamlet et al. (2020), with a study that showed a higher incidence of cognitive readiness behaviours in SAR aircrew than were displayed by their counterparts flying offshore transport. Therefore, the findings of the present study support the research of Hamlet et al. in suggesting that although cognitive readiness attitudes are reported as present in all mission types, they are more highly reported and applied in reactive missions and are likely to be a core skill implicit within highly reactive roles.

So what? The significance of operational differences to non-technical skills training

The growing body of work into non-technical skills has tended to treat specific industries or occupations as monolithic in their activities and, therefore, uniform in their behavioural and risk profiles. The development and mandating of CRM training within the aviation industry is an excellent example of this, with a single set of regulations covering how non-technical skills should be trained and assessed across all categories and kinds of civil aviation activity. In reality, operating differences between widely varying flying activities require the nurturing and development of different kinds of behavioural and attitudinal skills (Flin et al., 2017).

Evidence from the limited research specific to rotary wing shows that variations across mission types are particularly pertinent to helicopter operations (Hamlet et al., 2023). Some of these differences are more apparent than others. For example, differences between the tasks and profiles flown by helicopters compared to passenger airliners might be evident even to the layman, whereas the difference between operating a helicopter in a police or a SAR role is probably not, and is likely to be more nuanced.

Looking more closely at a given operation can reveal variations in specific attitudes and behaviours from one technical setting or operational sub-culture to another. The variation in operational unpredictability between types of helicopter-flying activity reported in this study is an example of how and why these differences can occur. This further strengths the case for making training more effective by tailoring it to an operational role. It also raises questions such as where cognitive readiness knowledge, skills, and attitudes might fit into the current range of defined aircrew competencies and – if these are trainable skills for emergency crews – how they can be developed.